My heart sank when Health minister Jeremy Hunt announced that league tables for surgeons would be published back in 2014. As a consultant surgeon at one of the UK’s leading teaching hospitals, I knew that he meant well but, as I expected, the new league tables have damaged patient confidence, undermined surgeons’ morale and mislead the very people who needed to know the truth.

His argument was this. Publish the 90 day mortality rates of surgeons and you’ll weed out the bad ones. The worse the surgeon, the more people die at his or her hands. So simple. But actually, a disaster that turned the truth on its head.

Let me be straight. I care passionately about the wellbeing of my patients. I think people deserve to have the best care given by skilled professionals. The government’s plan to publish a league table of surgeons was a good idea in theory – after all, transparency must be a good thing. Patients, armed with this information, should have been able to make informed choices. Surgeons should have been motivated to improve their performance and climb the ladder of success.

In my opinion, this new league tables have done precisely the opposite of what they intended.

Why is this? I’m not talking from the perspective of a surgeon who is low down the rankings. My mortality rates are considered acceptable and above average. But it’s just good fortune that I come out looking good when some of my most skilled colleagues are at the bottom of the list. They have been humiliated and forced to watch their hard-won reputations being trashed.

The data that they are basing their table on is so crude as to be meaningless. They look at 90 day mortality – end of story. In other words, does the patient you operated on survive for 90 days? It is age corrected but it is impossible to correct for all the circumstances that make a huge difference to survival rates. For example, I have had two deaths in elderly cancer patients within 90 days of surgery. Neither of these deaths were unexpected and my adjusted mortality rates look rosy. But a colleague who is universally recognised to be an outstanding surgeon has also had two deaths – but in younger patients. The fact that one had inoperable cancer and the other was dying of advanced lung cancer are not taken into account. His mortality rate has been deemed unacceptable which is completely wrong.

On the other hand, there are surgeons who have had very serious and avoidable complications around the time of surgery, but because the patients have limped on beyond the 90 day cut off, they come out with spotless reputations. And to add to the irony, the skilful surgeons who are going on the black list are the very ones that have often got these surgeons out of trouble.

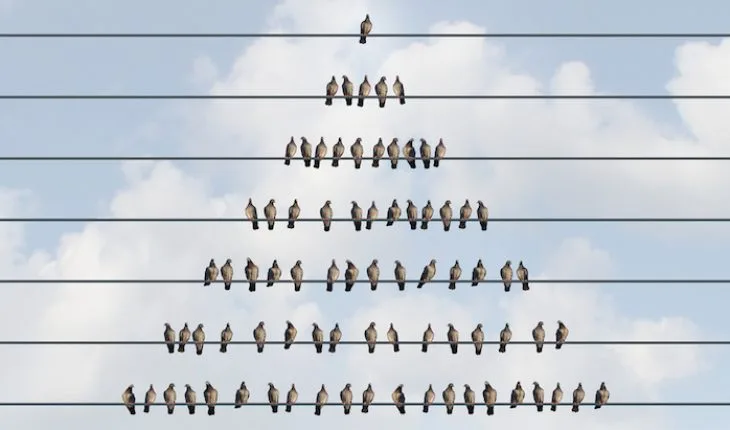

The fact is that some of the more skilled and dedicated surgeons deal with the hardest cases that less experienced surgeons shy away from. That is inevitably going to give them higher mortality rates. Surgery may be a last resort – almost a heroic attempt to hold back the inevitable. And sometimes, they really do save the day against all the odds.

Just think of the future too. Surgeons are already less inclined to take on difficult patients. To stay at the top of the league tables and preserve their reputations, canny surgeons will steer clear if they can. More than likely, a group of dedicated selfless professionals will end up looking after these desperate cases and get nothing but public opprobrium for their dedication.

Since the league table of cardiothoracic surgeons was introduced, there have been serious consequences for patients. I have heard that patients with high mortality risk now fill a surgeon with dread. Not only do they have to deal with the immense pressures of knowing that their best efforts may at best only produce a 20% survival rate but it is most likely that their failure to deliver survival will result in protracted and highly stressful confrontation with the coroners court. It may well be that at the end of the process it is accepted that everything that could humanly have been done was done but the process and stress of knowing that such a fate faces a surgeon every time he takes on a high risk case inevitably means that surgeons will wish to avoid such risk and decline to take on these cases.

By all means, introduce a league table, but make sure that it reflects the reality, not this mockery of a system that is already causing confusion, stress and anxiety. The successful outcome of surgery for a patients relies on so much more that the individual surgeon. Mortality should be reported by unit. A great unit will get great results because its surgeons work as a team, because they have access to the best equipment, because they are supported by great high dependancy services and they have great nursing services. This is what patients should be really being told about. Put the greatest surgeon in the world in a hospital with poor support services and his patients will do badly however beautiful the operation looked. And if you really want to now something about the surgeon then look in more detail at specific surgery related complications like blood loss, excessive operative times, failures in anastomoses and so on. This reflects skill far more accurately than 90 day mortality rates.

Everyone knows the old adage that there are lies, damned lies and statistics. Never has it been so true as in NHS surgical league tables.

- Tresiba® demonstrated significantly lower rates of overall, nocturnal and severe hypoglycaemia vs insulin glargine U-100 - 14th June 2016

- Legal headache for medics - 26th May 2016

- The shaming of Dr Issam Abuanza - 25th May 2016