Rebecca Wallersteiner visits a new art exhibition at the Sigmund Freud Museum, London which celebrates 160 years since the birth of the father of psychoanalysis and his complex family life

160 years after Sigmund Freud’s birth, today’s artists still remain fascinated by the father of psychoanalysis. From 30th September, The Freud Museum, London, will launch This Breathing House a new exhibition by London artist Bharti Kher exploring the family life of the father of psychoanalysis. This Breathing House will feature Kher’s new work which draws inspiration from the house which provided the Freud family with a refuge when they fled Nazi Austria in 1938. In 1940 the poet W.H. Auden wrote about Sigmund Freud, “if often he was wrong and at times absurd/to us he is no more a person/now but a whole climate of opinion/under whom we conduct our different lives.” Many decades after Auden wrote this poem Sigmund Freud remains as enigmatic and iconic as ever, although he is more appreciated in the arts than sciences. The building which now houses the Museum in Hampstead was formerly his home and that of his daughter, Anna, an eminent child-psychoanalyst, until it was turned into a museum after her death. Since then it has hosted many art exhibitions in recent years, which Freud (whose raffish, dyslexic grandson Lucian became a painter), would no doubt have appreciated.

Kher’s new exhibition is a dialogue with the house, exploring Freud’s family life as well as his theories. She overlays, subverts, conserves and erases memories – of herself and of her own life, of her family and of the people who lived here. Her new exhibition is a dialogue with the house, exploring Freud’s family life as well as his theories. She adds traces to the house of conversations past and present that also engage with Freud’s references to the mind as a complex energy system. The centrepiece of the Museum and another focal point of the installation is Freud’s extraordinary study, containing his iconic psychoanalytic couch, together with countless books and antiquities. The first work the visitor encounter upon entering the house is Bloodline (2000). Like a vein, this glowing red tower stands in the middle of the building, from floor to ceiling, binding the house together. Consisting of red glass bangles that recollect the sound of women moving through a space, it is an introduction to Kher’s idea of the house as a living breathing space.

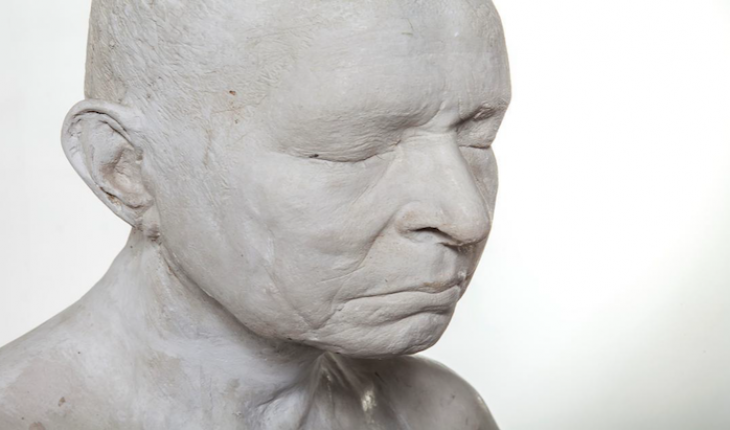

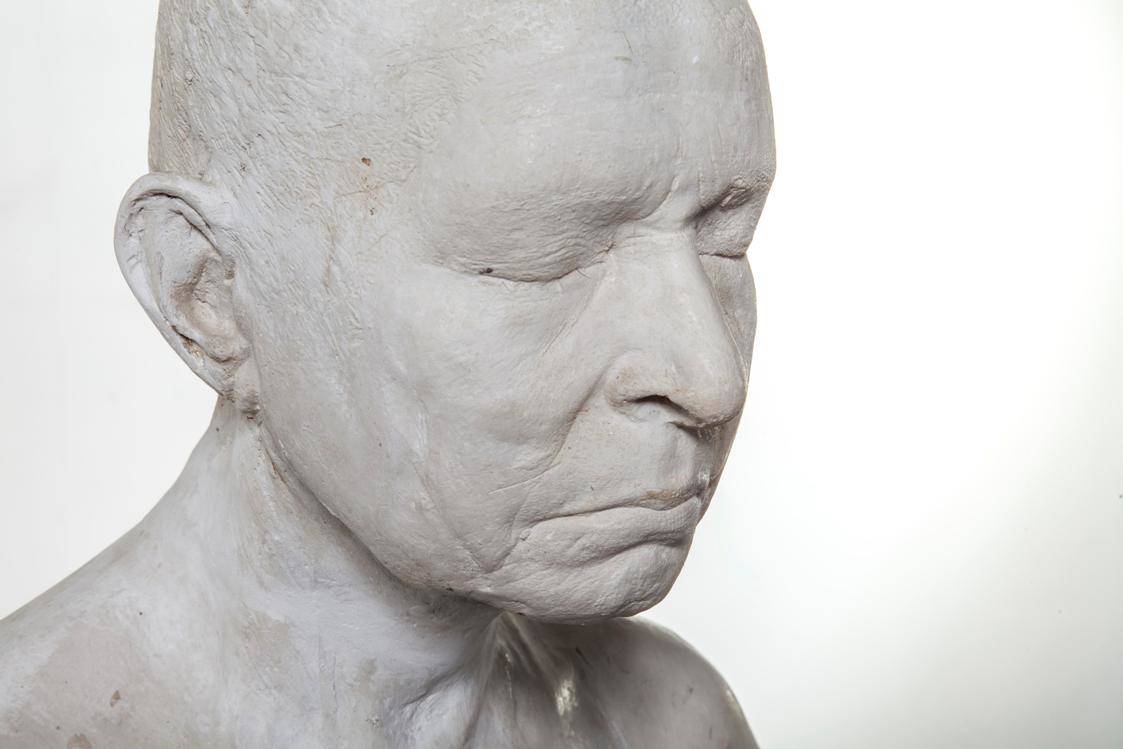

In Freud’s study are life-size casts of Kher‘s parents. These sculptures place Freud’s theories and material into a dialogue. They identify skin as the primary carrier of memory. Kher explains: “What was suggested through the casting of the skin, through the memory of this tactility of plaster and how it impregnates the skin and somehow takes the essence through the pores. … It’s almost as if you look away from somebody to understand, to hear them, to see them… You have to not use the eyes to see, you have to also remember and also somehow bring together your experience and forgive. You are trying to capture their breath, to find the imprint of their minds and thoughts and the secrets of the soul. Give me your essence and be light for that time. What the cast carries only the model can give.”

The materiality of body casting, conserving and preserving is continued in The Chimera series, as casts of faces of loved ones. But here the materiality of body casting, conserving and preserving is continued in The Chimera series, as casts of faces of loved ones. But here the positive is negated. Although imprinted into plaster the portrait is protected from the outside by wax. The features no longer visible are inverted and hidden. Kher has said of the process: “You take the first imprint of the skin and then you freeze it and then you cover it. So it is like a time capsule. You encase something to preserve it.”

The Intermediaries is interspersed with the antiquities that Freud himself collected. Kher describes the sculptures as “part secular and part deity. The clay sculptures are made in the South of India to be taken out once a year during festival time.” Perhaps mirroring many of Freud’s own ancient keepsakes some of them arrived broken and so the artist “began to see them as the broken idols … the ones that could no longer be worshipped or prayed to.”

With Equilibrium, a triangle hanging between floors, the artist draws us into impossible worlds: on one side of the coin there is mythmaking, and on the other, existential failure. Kher seems as preoccupied with the equilibrium of physical forces, as psychological. She achieves a “steady state” by a surreal conjunction of elements. Drawn from found and cast objects these works are strange tantalising conjunctions of disparate forms and things – all held together in a delicate precarious balance.

Sigmund Freud himself thought up many ideas that had occurred to no one before – which brings him close to the creative process of artists. Freud believed that sexuality and creativity lay at the centre of human being – an idea that artists are able to understand and develop.

Bharti Kher – This Breathing House (30th September – 20th November 2016)

Freud Museum, 20 Maresfield Gardens, London NW3 5SX, tel. 0207 435 2002 www.freud.org.uk

- People’s Choice Victory for Down’s Syndrome Scotland Garden at Chelsea 2025 - 28th May 2025

- Cadogan: A Chelsea Family By Tamsin Perrett - 3rd May 2025

- Dream Worlds a new exhibition in Cambridge - 14th December 2024