People affected by fatal snakebites in sub-Saharan Africa are in desperate need of affordable, quality antivenoms. Snakebite envenoming permanently disables hundreds of thousands of people and kills more than 100,000 each year all across the globe – more than any other World Health Organization (WHO)-designated neglected tropical disease – even though highly effective treatments exist. More than 20,000 people die from snakebites each year in sub-Saharan Africa alone. While Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) treats several thousand people free of charge in its facilities annually, most people who are bitten in sub-Saharan Africa live in rural areas and receive no treatment with antivenom (the only validated treatment for the disease), or receive substandard treatment because exorbitant prices put quality treatment out of reach.

Banywich Bone, 18 ans, was reffered to Agok From Mayom, where MSF runs a primary health center. He was bitten by a snake three years ago, while he was sleeping at home. When he arrived in the hospital, he presented an infected wound for which doctors blame the snake bite. His left leg had necrotic tissus and pain, the wound was infected and MSF surgeon had to amputate the leg above the knee.

Fortunately, in March 2017, the WHO classified snakebite as a neglected tropical disease of the highest priority. This year, the WHO will launch an ambitious roadmap to reduce snakebite-induced death and disability. The roadmap will seek to address the lack of access to effective, quality antivenom treatment – one of the main obstacles MSF encounters treating people in places such as South Sudan, Central African Republic and Ethiopia.

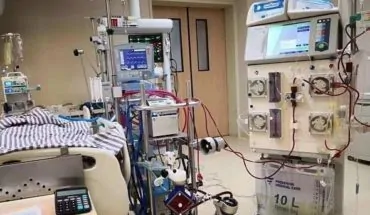

Antivenoms are medications derived from plasma of horses that are ‘hyperimmunised’ with snake venoms. People bitten by snakes receive antivenom intravenously. The severity of snakebite envenoming determines the dosage of antivenom administered – or the number of vials each person needs.

Antivenoms are medications derived from plasma of horses that are ‘hyperimmunised’ with snake venoms. People bitten by snakes receive antivenom intravenously. The severity of snakebite envenoming determines the dosage of antivenom administered – or the number of vials each person needs.

Right now, in most African countries, people need to pay for treatment out-of-pocket, making it practically inaccessible in impoverished rural settings where most people at risk live. An effective, quality antivenom treatment often costs several times what people earn in an entire year. In severe cases requiring several antivenom doses, the price of a full treatment can exceed US$200. Due to high prices of quality antivenoms, people are often lured into purchasing cheaper products that are of questionable quality, safety and effectiveness, further contributing to the high rate of death and disability from snakebite.

So, what needs to be done to tackle this crisis? A strong commitment to the WHO roadmap is needed at the national, regional and global levels to enable substantial improvement in access and availability of effective quality antivenoms. Antivenoms must be available to people free of charge – or at a very low price – to help those affected by this deadly disease. This would mean:

1. More people will have access to lifesaving treatment

The proportion of snakebite victims in Africa accessing any antivenom treatment (including ineffective treatment) is very low. The high price of antivenoms means most people who are bitten opt for traditional healers (cheaper) before going to the hospital, although none of the traditional methods to treat snakebite are proven to be effective. If quality treatment was available for free or at a very low price, people would be more likely to seek effective care sooner.

2. Substandard antivenom products will be phased out from the market

The African market has been dominated by a few substandard antivenom products because their unit price is lower than that of effective quality products. If quality antivenom products are subsidised by WHO member states, making them available for free or at a very low price for those who need it, the production of substandard alternatives will not remain a viable business.

3. Antivenom will be seen as a preferred treatment in sub-Saharan Africa

The use of poor-quality products has made healthcare workers and communities hesitant to use antivenom for treatment as many cases of ineffective products have been reported. Better access to effective, quality treatment options is crucial to restore people’s belief that treatment using antivenoms is the best treatment for snakebites.

4. People bitten will be treated with the right dosage

The number of vials needed to treat a snakebite depends on the quantity of venom a person was injected with when bitten and the potency of the antivenom product that is used. Often, people do not receive the recommended dosage of antivenom because they can only afford part of the treatment course. People need the dosage that will prevent disability and death, not simply the dosage they can afford.

5. The number of African suppliers of effective, quality antivenom will increase

Although the number of cases of snakebite requiring treatment is believed to be fairly stable, the African antivenom market has fluctuated over time. Several suppliers of effective quality antivenom have stopped production because their market shares declined or stagnated. Fav-Afrique, produced by Sanofi-Pasteur, is the latest example of a much-needed product being discontinued. If the supply and availability of effective quality antivenoms was subsidised, securing an economically viable price for the producers, demand for effective quality treatment would increase.

The WHO is currently assessing a number of existing antivenoms intended for use in sub-Saharan Africa as a first step towards determining what makes an effective, quality antivenom, and identifying which antivenoms available on the market are not effective and should be phased out. Because eliminating or dramatically reducing out-of-pocket expenses for victims of snakebite is so critical to tackling this crisis, the development of an international financing mechanism for global procurement and supply of affordable, quality assured antivenoms should be the next step. To save lives, countries and donors must act now by supporting an international financing mechanism for antivenoms and by including snakebite treatment in universal health coverage policies.

Villagers try to kill a snake in a village in the region of Paoua, northwestern Central African Republic.

To ensure a robust global response to snakebite, the WHO, countries and donors must also commit to:

• Supporting research and development of new and better snakebite treatments and diagnostic tools;

• Improving training for healthcare professionals and community awareness of snakebite first aid and prevention;

• Building evidence on the actual number and distribution of snakebite cases in different regions; and

• Intensifying work to control the quality of antivenom products.

During the WHO Executive Board meeting in Geneva this month, Member States will discuss a proposed resolution on snakebite that will be submitted for approval by the World Health Assembly in May. The proposed resolution and WHO roadmap represent a major opportunity. It is time for governments and donors to harness this momentum and prevent unnecessary death and disability from snakebite once and for all.

- Antivenoms needed in sub-Saharan Africa - 23rd January 2018